A study published in 2021 revealed ancient human footprints that lined White Sands National Park in New Mexico. Initial analyzes suggested that these tracks were imprinted into the ground between 23,000 and 21,000 years ago, making them the oldest known fossilized footprints left by humans in North America. But not everyone agreed with these estimates, especially because of the dating technique used. But in a new study, researchers used two other methods and reached the same result.

When did the first humans arrive in North America?

It has long been accepted that humans spread to North America at the end of the last ice age, as evidenced by the oldest known tools dating back about 13,000 years (Clovis technology) found in what is now the state of New Mexico. At that time, the retreat of the glaciers would have made it possible to open a corridor in the Bering Strait.

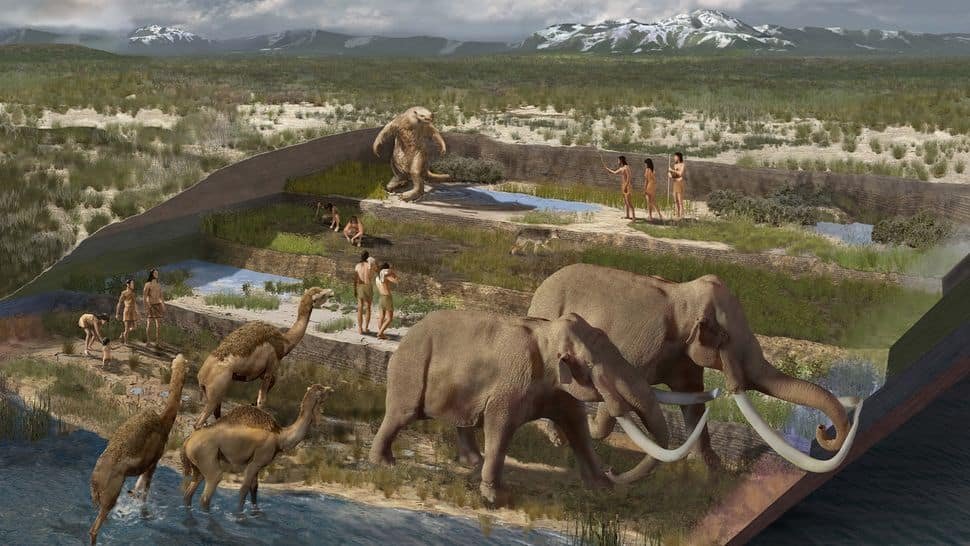

Two years ago, however, this idea was called into question after the discovery of footprints in White Sands National Park, many of which were made by children, approximately 23,000 years old. At that time, these people would have evolved on moist, sandy soil at the edge of a lake. Later, sediment slowly covered them before hardening. Erosion would then have exposed them again.

To achieve these results, the researchers collected ancient seeds from different layers of sediment that once grew on the edge of the same lake at the same time. By measuring the carbon they contained, they found that these plants had been growing thousands of years before the end of the last ice age, which between 22,800 years and 21,130 years.

A method criticized

However, not everyone agreed with these results. Last year, a group of archaeologists pointed out that the radiocarbon-dated material used in the first paper is the seeds of the water plant. Ruppia cirrhosawas not reliable. As a reminder, dating radiocarbon is based on determining the amount of carbon-14 present in an organic sample, which makes it possible to estimate its age in relation to the amount of carbon-14 in the atmosphere. However, in the case of the aquatic plant Ruppia cirrhosathis dating method can be misleading due to its carbon source.

Unlike many organisms that breathe air and incorporate atmospheric carbon-14 into their organic structure, Ruppia cirrhosa actually obtains its inorganic carbon for photosynthesis from water. By using the carbon dissolved in the water, this plant forms organic molecules whose carbon is devoid of carbon-14, because water generally does not contain this element in significant quantities.

When we thus make a dating of this kind on the seeds of Ruppia cirrhosathe levels of carbon-14 present in these seeds may appear lower than would be expected for organic samples of a given age. But lower levels can give the impression that the sample is older than it actually is.

Two other methods confirm the assessment of the age of the prints

In this contraction study, the researchers proposed the use of another method, called optically stimulated luminescence (OSL). Basically, this technique estimates the time since quartz or feldspar grains were last exposed to intense heat or sunlight. In this new work, that’s exactly what the researchers did. They then found that the layers bearing the prints had a minimum age around 21,500 years.

This team also isolated and radiocarbon dated three soil samples, each containing 75,000 grains of conifer pollen from the same imprint layers as the Ruppia seeds. This time we know that these plants get their carbon-14 from the atmosphere, not lake water. Here again, the age corresponded to that of the quartz grains. So the debate is closed. Humans were actually present in North America since at least 21,500 years ago and potentially around 23,000 years agoalmost 10,000 years earlier than expected.

These discoveries are revolutionizing our understanding of human history in North America, not only by pushing back the date of the arrival of the first inhabitants, but also by opening the door to new hypotheses about the modes of migration and adaptation to the ‘environment’. These early humans would have survived in extreme climatic conditions while the region was still heavily affected by the last ice age. This research shows that scientific methods are constantly evolving, allowing for a re-evaluation of past data and a better understanding of ancient societies.

Details of this new work are published in the journal Science.